| Commemorating the 500th Anniversary of the Arrival of the Horse to the Mainland of the Americas |

Leonardo da Vinci, the Horse, and the American Mainland

|

1519-2019

By Louis E.V. Nevaer

|

|

| Leonardo da Vinci |

|

|

|

| The Horse |

|

|

|

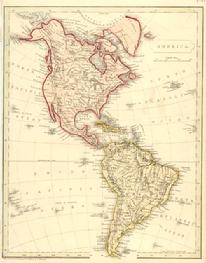

| The American Mainland |

|

|

This year, 2019, marks the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci, who was fascinated by horses all his life. It also marks the first time a horse set hoof on the American mainland. As it happens, the Italian Renaissance master died the same year that the horse arrived in the New World.

In April 1519, Hernán Cortés set sail from Cuba for Mexico, landing on Cozumel Island, off the Yucatán peninsula. His fleet consisted of eleven ships carrying some five hundred men and slaves and sixteen horses. It was there that the first horse disembarked in the Americas when they crossed to the shores to reach present-day Playa del Carmen.

There, in the Yucatán, Cortés learned that two Spaniards, shipwrecked when the Santa María de la Barca sank during a storm six years earlier, had survived. Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero had learned the Maya language and culture during their capitivity. Guerrero had married Zazil Há, a Maya woman, with whom he had children. He refused to be rescued and join Cortés, turning his back on his countryman. Cortés was infuriated, telling his compatriots, “Truthfully, I want him in my hands because it is not a good place to leave him.” The other, Gerónimo de Aguilar, was eager to leave the Maya and return to his world; he joined his compatriots and would become an invaluable translator and cultural interpreter for Cortés. One Spaniard remaining and the other rescued, the expedition sailed around the peninsula and into the Gulf of Mexico, making landfall near present-day Tabasco.

|

Across the ocean, the following month, Leonardo da Vinci, at the age of 67, died in Amboise, Kingdom of France. The Italian Renaissance master, long enamored of horses, had spent decades using the horse as his subject and inspiration. As early as 1482 he had submitted an ambitious proposal to Lodovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, to create a monumental sculpture of the horse. Da Vinci’s Il Cavallo would be an enormous casting in bronze, a horse to stand guard over the Duke’s castle in honor of the Duke’s father, Francesco Sforza. For almost two decades, this project testified to da Vinci’s obsession with horses. Il Cavallo would stand 24 feet tall and require 70 tons of bronze for the casting. A full-size clay model of his proposed sculpture was created, but politics interfered. France’s Charles VIII advanced on the Italian kingdoms and duchies; the Duke of Milan was forced to divert resources for weapons. In September 1494, Charles VIII invaded the Italian peninsula, his troops taking Pavia in October and, a month later, Pisa. The Republic of Florence welcomed the French, believing they would rid the city-state of corruption. With such an exuberant welcome, Charles VIII pushed farther, with greater resolve and speed. Naples fell without much resistance; Alfonso II was expelled, making way for Charles VIII to be crowned King of Naples. Alarmed, Pope Alexander VI and Ludovico Sforza formed an anti-French coalition, the League of Venice, on March 31, 1495. Charles VIII was, however, unstoppable: Milan fell without a fight four years later. The victorious French archers, astounded by da Vinci’s clay horse, delighted in using it for target practice, reducing it to a pile of shards.

The destruction of the sculpture he dreamed of haunted da Vinci for the rest of his life and weighed on his mind that spring day in 1519 when he passed to eternity.

|

If da Vinci appreciated the beauty and grace of the horse, Cortés understood its power over the human imagination.

In 1493, Christopher Columbus returned to the island of Hispaniola, today shared by the Dominican Republic and Haiti, with livestock—and horses. Cortés arrived in Santo Domingo, the capital of Hispaniola, in 1504 when he was eighteen years old, an accomplished horseman and well-liked member of the fledging community. Governor Nicolás de Ovando appointed him notary of the town of Azua de Compostela, granting him an encomien, which allowed him land to farm, raise horses, and build a home. He proved himself an exceptional settler and was invited to participate in the conquest of Cuba two years later. By 1509 Cortés had been granted a large estate and numerous slaves in Cuba.

The Spanish realized the importance of horses in securing their safety as they established permanent prosperous settlements.

Over the next decade, Cortés championed the horse as the defining advantage in establishing Spanish authority over the new lands the Spanish claimed. By the time he arrived on Cozumel in 1519, he understood that a Spaniard, dressed in regalia, wearing the iconic morion, or helmet, astride a horse was an intimidating sight.

|

| From the Ice Age to Our Age |

Equines in the Americas had been extinct since the prehistoric Ice Age; no one in any of the indigenous societies the Spanish encountered had ever seen such a creature.

The horse, not surprisingly, was a source of astonishment—and controversy. Contemporaneous accounts among the Maya, for example, reveal the confusion. The Yucatec Maya, whom Cortés encountered on Cozumel, recognized the horse as a strong and formidable animal. The Chontal Maya, whom Cortés would encounter when he circumnavigated the peninsula and landed in modern-day Tabasco, were convinced, on the other hand, that horse and rider were one being—a two-headed god.

All the indigenous people were in agreement on one point: they marveled at the Spaniards’ ability to tame such a creature.

This was not surprising. The beauty and grace of the horse had always inspired flights of fancy. When Ludovico Sforza married Beatrice d’Este, da Vinci deferred to the fabulist magnificence of the horse in his notebooks: “First a wonderful steed appeared, all covered with gold scales which the artist has colored like peacock eyes. Hanging from the warrior’s golden helmet was a winged serpent, whose tail touched the horse’s back. Above the helmet place a half globe, this is to signify our hemisphere. Every ornament belonging to the horse should be of peacock feathers on a gold background, to signify the beauty which comes of the grace bestowed on him who is a good servant.”

To the inhabitants of the American continent who first saw the horse, it must have appeared as magnificent as da Vinci envisioned: Cortés conveyed effortless superiority.

This was the reason Cortés went about on horseback, a morion helmet on his head: the image of unchallenged power and tranquil assurance. Decades before, the same was said of da Vinci’s Italy: Leon Battista Alberti, an Italian author, architect, and poet, wrote: “One must apply the greatest artistry in three things: walking in the city, riding a horse, and speaking, for in each of these one must try to please everyone.”

Cortés and da Vinci were masters of all three.

|

| The Impact of the Horse on the Imagination of the Indigenous Peoples |

Soon after Cortés disembarked on Cozumel, he realized the powerful advantage he had with Gerónimo de Aguilar by his side: the indigenous peoples knew nothing of Europe, but Cortés now had insights into the technology, weapons, politics, and rivalries of these societies. Aguilar provided strategic insights: No metal weapons. No beasts of burden. No use of the wheel. No literate man or woman for hundreds of miles. No love for the Aztecs.

When asked to explain the people and this land, Aguilar, by then fluent in Yucatec Maya, was able to tell Cortés that “some unknown calamity” had befallen these societies. When pressed, Aguilar told Cortés that none among the Maya could read or write—and that they had forgotten their own histories. When Cortés asked the Maya who could read the glyphs and inscriptions adorning temples and monuments, the answer was always the same: “Who knows?” When asked about their own history, no one could offer anything other than myths involving magic.

Cortés also delighted in the realization that the Maya were fascinated with the horse.

If da Vinci understood how to make solicitations of support from rich and powerful patrons, Cortés knew his success would depend on the horse. Two previous expeditions, those of Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, in 1517, and Juan de Grijalva, in 1518, after all, had failed; neither man had brought along horses. Cortés had a strategic advantage and he knew it.

The arrival of the horse on the mainland of the Americas thus changed the narrative of history, on both sides of the Atlantic.

|

| Your Aztec Emperor . . . for a Horse |

|

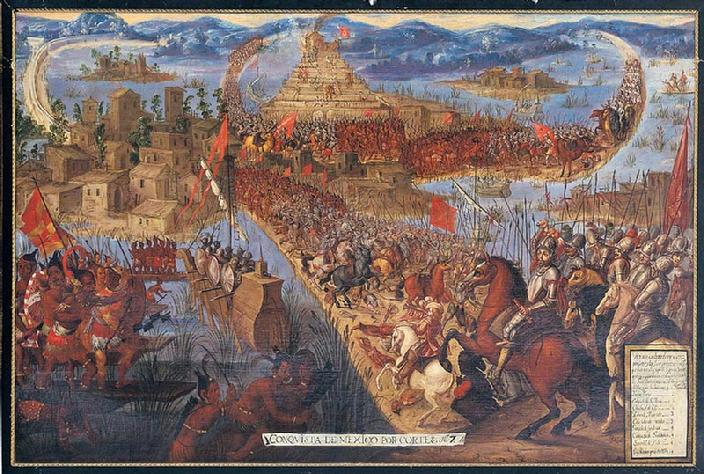

| The Conquest of Mexico by Cortés gives the horse a starring role, more prominent than the pyramids and temples of the vanquished Aztec capital. |

|

|

Cortés masterminded and executed the military defeat of the Aztecs, of course, but it would have been impossible for 500 men to vanquish tens of thousands of Aztec warriors. Mexico City fell because of the fierce armies comprised of Cempoalan and Tlaxcalan warriors who fought under the direction of Cortés, directing the battle on horseback.

Cortés, of course, took credit for “conquering” the Aztecs; he knew the importance of image in establishing Spanish authority both to the subjugated indigenous peoples and the rival European powers back home. He also reserved the right to possess a horse to only the most loyal among the native allies; Xicomecoatl, the leader of the Cempoala, who first joined Cortés, was rewarded with a horse.

|

|

| Commissioned by the Spanish during the first century of Spanish rule, the Codex Azcatitlán depicts the horse, center stage, as the Spanish-Tlaxcalan armies, led by Cortés and La Malinche, his interpreter and mistress, march to Mexico City. |

|

|

|

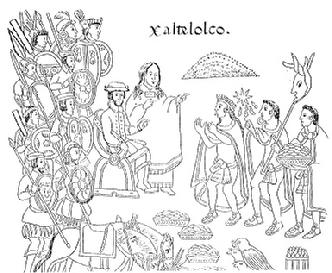

| A scene from Diego Muñoz Camargo’s History of Tlaxcala, c. 1585, shows Cortés granting an audience to three indigenous rulers: allegiance to the Spanish crown for a horse. |

|

|

| The Horse and Hispanization |

The arrival of the Spanish heralded liberation for scores of indigenous societies that had been subjugated by the Aztecs. The Aztec Empire, it should be noted, was a euphemism, for in fact it was a triple alliance comprised of city-states: México-Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tlacopan.

Cortés understood that to govern this vast land and its competing, bickering, rival societies that he had further fractured, there would have to be comprehensive alliances that respected the existing pre-Hispanic sociopolitical structures. Spain would extend its rule more through co-opting than through military conquest. On two things, however, there would be no compromise: allegiance to the Spanish crown and conversion to Christianity. This meant that Spanish would become the lingua franca throughout New Spain and that the Roman alphabet would be used as the common writing system. Once the King of Spain gave Cortés the title of Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca, he wasted no time in establishing alliances with the various indigenous constituencies.

To the indigenous elite aligned with Cortés, the preservation of their social prestige, material wealth, and political hegemony was paramount. What better proof that they were favored by the Spanish than the right to own horses?

Equines conferred social status and signaled unwavering support from Cortés.

For their part, the Spanish respected the existing norms, imposing the cabildos over the pre-Hispanic city-state (or altepetl) governing structure. The result was one in which the Spanish, in essence, returned local control and continuity of power to the indigenous communities, affording them localized self-government. This assured Pax Colonial, despite localized uprisings, and the system of semiautonomy functioned effectively until Mexico’s independence from Spain.

The importance of Spanish missionaries’ work in preserving indigenous societies is often overlooked. Bernardino de Sahagún, for instance, translated the Psalms and the Gospels into Náhuatl and today is considered the father of anthropology itself. And the list goes on: the Spanish launched modern social disciplines from Maya Studies to American Ethnography, modern linguistics to New World epigraphy, inventing, along the way, the fields of cross-cultural studies.

Forty percent of every document that survives to this day was, in fact, commissioned by the Spanish. This was only possible because the Spanish introduced the Roman alphabet so as to teach indigenous scribes to read and write; the horse was often used as an incentive to convince indigenous rulers to speed up Christianization, which meant literacy.

|

| Commissioned by His Majesty, the King of Spain |

Three documents, out of thousands, serve to demonstrate the emergence of a post-Hispanic society in which the Spanish taught the indigenous people how to memorialize their stories, perspectives, and histories.

|

|

| Cristóbal de Olid, on horseback, leading the Tlaxcalan allies in battle to establish Spanish authority over Jalisco and Colima, northwest of Mexico City. Commissioned by the Spaniards around 1522, the text consists of the Roman alphabet, reflecting the role of Spanish Catholic Franciscans, Jesuits, Augustinians, and Dominicans in spreading Christian doctrine through literacy campaigns. |

|

|

|

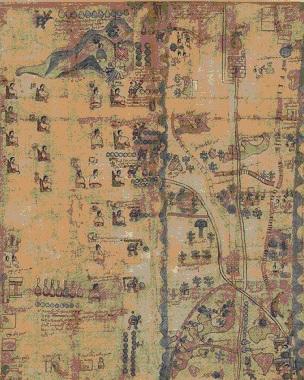

| Commissioned by the Spanish around 1540, the Códice del Cristo de Bornos, discovered in Cádiz, Spain, documents the paramount post-Hispanic importance on memorializing pre-Hispanic America. The text combines both pictorial Náhuatl glyphs and the Roman alphabet, reflecting the role of Spanish Catholic Franciscans, Jesuits, Augustinians, and Dominicans in spreading the Christian doctrine through literacy campaigns. |

|

|

|

| Commissioned by the Spaniards in 1593, the Codex Quetzalecatzin depicts the evolution of indigenous societies after contact with the Spanish. The text combines pictorial Náhuatl glyphs and the Roman alphabet, reflecting the role of Spanish Franciscans, Jesuits, Augustinians, and Dominicans in spreading Christian doctrine through literacy campaigns. |

|

|

The horse, in fact, as much as the Roman alphabet, accelerated the Hispanization of indigenous societies in what would become New Spain as Spanish rule expanded across the hemisphere (Viceroyalty of Perú (1542–1824); Captaincy General of Chile (1541–1818); Viceroyalty of New Granada (1717–1819); Captaincy General of Venezuela; and Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata).

The power of the horse, however, could not be contained to Spanish America.

|

| Beyond New Spain: Cultural Appropriation |

The Spanish ventured forth, north of the Caribbean and the Valley of Mexico, in expeditions of exploration, discovery, and encounters. Ponce de León circumnavigated the Florida peninsula in 1513, from present-day St. Augustine down to the Florida Keys and up to the Tampa Bay area. He returned in 1521 with horses and livestock, establishing a colony near Charlotte Harbor. Pánfilo de Narvaez brought several dozen horses when he established a colony near present-day Tampa around the same time. Hernando de Soto arrived near Tampa Bay in 1539 with approximately 200 horses. From there de Soto traveled north and west, exploring the present-day Carolinas, Tennessee, and Alabama before turning west into present-day Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas.

In the decades that followed, the Spanish would establish the oldest city in what today is the United States. On September 8, 1565, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés arrived with about 800 men and women, horses, and livestock and founded Saint Augustine. A month later, he invited the neighboring indigenous communities to celebrate the first Mass of Thanksgiving. The feast consisted of salted pork and typical Spanish products such as red wine, olives, oranges, bread, and chickpeas. Decades later, the Pilgrims would emulate the Spanish example in their first Thanksgiving when the fledging community invited their indigenous neighbors to a feast in October 1621.

By the 1560s, Spanish horse culture became established in Florida, an outpost on the periphery of New Spain.

|

| Northern Reaches of New Spain |

The same was true of the vast stretches of frontiers north of the Valley of Mexico.

Francisco de Coronado embarked on an expedition in 1535 that lasted until 1542, exploring, at first, what is now Arizona and New Mexico. He and his men continued on and were the first Europeans to reach the Grand Canyon, Oklahoma, Kansas, and West Texas. Coronado brought along 558 horses, including mares.

The equines astonished the indigenous peoples they encountered. It would not, however, be until half a century later when, in 1592, Juan de Onate established a colony in present-day New Mexico that the horse was introduced into the lives of the indigenous peoples west of the Mississippi and north of Mexico. Juan de Onate arrived with 7,000 head of livestock. His herd of horses consisted of mares and stallions.

Spanish ranchers throughout New Spain, not unexpectedly, introduced the traditions they had cultivated over centuries on the Iberian peninsula: free-range livestock that was rounded up only as needed, and allowing horses to breed freely. In this process, natural selection gave rise to the horse today known as the Galiceño.

From a distance, the indigenous peoples coveted the magnificent horse the Spaniards, few in number in the vast stretches of frontier, commanded: the horse, they knew, would be theirs.

|

| Cultural Appropriation by Native Americans |

|

| Spotted Tail, and his horse |

|

|

|

| Blackfoot Warrior, painted by Karl Bodmer |

|

|

|

| Native Americans, painted by David Mann |

|

|

|

| Lakota men on horseback |

|

|

When Coronado encountered the Plains Indians, he was careful to account for all his horses; only the Spanish could own a horse. He feared, however, that it would be a matter of time before that changed. And he was right.

The horse became a transformative event in the evolution of the societies occupying the northern reaches of New Spain. It is no overstatement that societies predating the arrival of the Spanish can divide their histories into the time before and after the cultural appropriation of the horse.

The indigenous societies that became fully nomadic after the arrival of the horse include the Blackfoot, Arapaho, Assiniboine, Cheyenne, Comanche, Crow, Gros Ventre, Kiowa, Lakota, Lipan, Plains Apache (also known as the Kiowa Apache), Plains Cree, Plains Ojibwe, Sarsi, Nakoda (Stoney), and Tonkawa. Once relegated to following vast herds of buffalo, after the horse had been culturally appropriated these societies were, by the 1800s, fully nomadic. Semisedentary societies, including the Arikara, Hidatsa, Iowa, Kaw (also known as the Kansa), Kitsai, Mandan, Missouria, Omaha, Osage, Otoe, Pawnee, Ponca, Quapaw, Wichita, and the Santee Dakota, Yanktonai and Yankton Dakota, enjoyed greater standards of living because of the horse. For these indigenous societies, living in villages and raising crops transformed their economies as the horse became a valuable resource in their commerce and trade.

In fact, as early as 1659 the Navajo began to raid the Spanish colonies for horses. When the Spanish were driven out of New Mexico, the Pueblo people seized thousands of horses and livestock abandoned and lost in the hurried retreat. When the Spanish attempted to reassert their authority over these territories in 1683, they found that the indigenous people had fully mastered the horse. Seven years later, the horse had become an integral part of the societies of the indigenous peoples along the mouth of the Colorado River in Texas. By 1685 the Caddo of eastern Texas were in possession of horses as well.

But it was the Comache who were among the first, as early as the 1730s, to appropriate Spanish horse culture completely and become accomplished horsemen. This astonished the French, who had ventured forth, sailing up the Mississippi River from New Orleans, their colony on the American mainland, founded in 1718. French explorer Claude Charles du Tinse, the following year, found that the Wichita of the Verdigris River possessed hundreds of horses. His compatriot, Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont, reported, in 1724, that the Kaw of present-day Kansas were also trading in horses. Within a decade, the horse was the most coveted possession of the Shoshone people in present-day Wyoming and the Blackfoot Confederacy, which extended into lands that are now part of Canada.

This unacknowledged cultural appropriation became so complete that today it is almost impossible to envision any of the indigenous societies of North America without the horse, a possession of prestige, utility, and wealth.

|

|

| Mexican Vaqueros |

|

|

| Cultural Appropriation by Anglophone Americans |

|

| American cowboy |

|

|

|

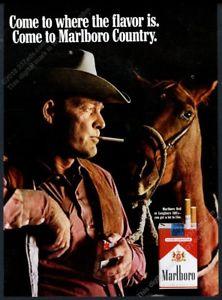

| Marlboro Man |

|

|

The Dutch, English, French, and Portuguese also brought horses to the Americas. The cultural traditions they brought with them, however, reflected the traditions of Western Europe, a landscape where deserts were absent. Consider, for example, the American Revolution. In 1777, George Washington established the Corps of Continental Light Dragoons. Congress asked two European nobles—Michael Kovats and Casimir Pulaski, of Hungary and Poland respectively—to create the United States Cavalry. American horse culture thus would remain Eurocentric until Americans crossed the Mississippi River.

In New Spain, geography shaped the evolution of horse culture throughout this hemisphere. The first “cowboy” was Eusebio Kino, a Jesuit priest who, in 1687, arrived in California and set up a ranch to serve the economy of the missions. Less than a century later, Juan Bautista de Anza led two expeditions, the first in 1769 and the second in 1774, in which Spanish-Mexican ranchers and ranching became fully established. This uniquely Mexican horse culture became known as vaquero throughout northern Mexico and in what is now the southwestern United States. (In the Jalisco and Michoacán regions, a distinct and stylized version evolved: charro.) The vaqueros and charros influenced other areas of Spanish America where there were vast open spaces and deserts, specifically Chile and, most of all, Argentina.

Only when Anglophone Americans traveled west of the Mississippi did they become aware of the Mexican vaqueros—to their astonishment. New England merchants either sailed around the continent to California or traveled overland along the Southwest in what became known as the Santa Fe Trail. These encounters with the vaqueros, reflective of the values and lifestyle of the frontier and wide-open spaces, captured the Anglophone imagination. American merchants returned to the Eastern seaboard with hides, tallow from the Mexican frontiers, and silver pesos. (The Spanish/Mexican silver peso circulated in the United States as legal tender until the Coinage Act of 1857.) They also returned with fantastical tales of the new breed of horseman and horse culture.

After the Mexican-American War in 1848, the border “crossed” vast territories where the Mexican vaquería culture flourished. Mexicans, overwhelmed by the newly dominant Americans, watched as the United States appropriated horse culture and made it their own, and the “American” cowboy was born.

Americans contributed only two things to the vaquero tradition: Levi’s denim jeans and the Stetson hat. In 1847, Levi Strauss, a German Jew who emigrated to California, began a supply company for the men rushing to find their fortunes once gold was discovered in northern California. He and Jacob Davis invented and patented the riveted denim pants, which became as popular with ranchers as they were with miners. Six years earlier, in Philadelphia, John Stetson invented the “Boss of the Plains” hat and the Cavalry hat. A prospector in Colorado panning for gold, he had invented the beaver felt hat for himself, and when he returned to the East Coast, he understood the needs of the men out on the frontier. He was right.

Americans thus replaced cloth pants with denim jeans and the Spanish sombrero with the Stetson, but everything else about the “cowboy” constitutes complete and unabashed cultural appropriation of the Mexican vaquero.

Of course, twentieth-century mass media and advertising transformed the image of the cowboy. Philip Morris introduced the Marlboro brand in 1924 as a woman’s cigarette. It fared poorly until the Chicago advertiser Leo Burnett repositioned it as a man’s cigarette. The “Marlboro Man,” introduced in an advertisement in Life magazine in 1949, became an iconic image that captured the American imagination.

The association of the cowboy with the exuberant masculinity of the frontier proved seductive, especially after it was reinforced by Hollywood in films such as The Magnificent Seven and television programs, including Bonanza.

The cultural appropriation was so complete that, today, most Americans believe the cowboy is an American creation.

|

| From the New World to the Old World |

|

| Ignacio "Nacho" Figueras |

|

|

Horse culture, over half a millennium, spread from Alaska to Patagonia with breathtaking success.

It’s not surprising, then, that when Ralph Lauren, sartorial heir to Levi Straus, launched his Polo menswear line in 1968, he wanted to associate his brand with the outdoors, rugged individualism, the wide-open spaces—and horsemanship. It is also not without irony that Lauren, based in New York, found his ideal brand manager at the far end of the continent: Argentine polo player Ignacio “Nacho” Figueras. From pole to melting pole, horse culture has become indelible to the Americas.

This would have pleased da Vinci. It would have also delighted him that in the Americas his Il Cavallo, a tribute to the magnificent beast the Italian master so loved, came to dominate. In 1977, amateur artist and pilot Charles Dent read about da Vinci’s horse in National Geographic. Inspired, he founded Leonardo da Vinci’s Horse, Inc., a nonprofit organization whose mission was to build the sculpture. He died in 1994 before his dream could come true; his nephew, Peter Dent, carried on his uncle’s vision. He commissioned Nina Akamu, a Japanese-American sculptor, to create a sculpture based on da Vinci’s drawings, sketches, and notes. Two full-size casts were made, one for Italy and the other to remain in the Americas.

Five years later, on September 10, 1999, The Horse was unveiled to much fanfare at the Hippodrome de San Siro in Milan, where it stands today.

This gift from the New World to the Italian Renaissance master was, of course, a poetic tribute to da Vinci and his love for the horse, begun 500 years ago when the first equine set hoof on the mainland of the Americas.

|

|

| Il Cavallo |

|

|

|